Chamberlain Democracy Digest | August 19

The team at the Chamberlain Network is pleased to bring you the Chamberlain Democracy Digest – a collection of what we’re reading and thinking about in the democracy space. Some weeks we’ll publish on a theme, while others will be a general round up.

In the lead up to Election Day, The Chamberlain Network is taking a deep dive into U.S. elections and the civic activities that lead up to them. Our hope is to empower all of you to be the voices of truth in your communities. As our democracy rests on trust in our electoral processes, we want to help you build that trust and counter the rumors and disinformation that have become more prevalent in recent years.

Since the Democratic National Convention kicks off this week, we thought political conventions would be a great place for us to start.

If you want to jump ahead, here’s an overview of what we’ll cover:

How were the Democrats able to change their nominee from Joe Biden to Kamala Harris?

Why did the Democrats hold a virtual roll call vote in advance of the Democratic National Convention?

Chamberlain Chit Chat (what our staff wants to share this week outside the democracy space)

How did political conventions start?

The U.S. Constitution has no specific provision for naming political candidates, yet a system for doing so has developed over time. There’s a long history of conventions that dates back to 1824 – when the congressional caucus system fell apart, no candidate was able to win the Electoral College majority. The contested election was handed over to the House of Representatives, and led to a revived two party system and the tradition of party nominating conventions.

Why do we have political conventions?

Every four years, each political party selects a presidential and a vice presidential candidate to represent that party in the general election in November. They formally do this at a political convention held in the summer before the November election.

While historically conventions served as the main way to select a candidate for president, these days they act as a formal acknowledgement of the decision of party voters who express their wishes through primary elections

Before party conventions, each political party holds presidential preference events – mainly primary elections, though a few states have caucuses – in each of the 50 states, Washington, D.C., and a handful of territories (see an overview of primaries from The Council of State Governments here).

Candidates win state delegates based on their performance in these primaries. To be a party’s nominee, a candidate needs a majority of delegate votes at the convention.

These delegates, along with super delegates (see below for an explanation), then attend their party’s presidential nominating convention on behalf of their state or community.

The conventions then serve, as the Brookings Institution explains, as “the legal authority that nominates a party’s candidate for President of the United States.”

What are delegates and superdelegates?

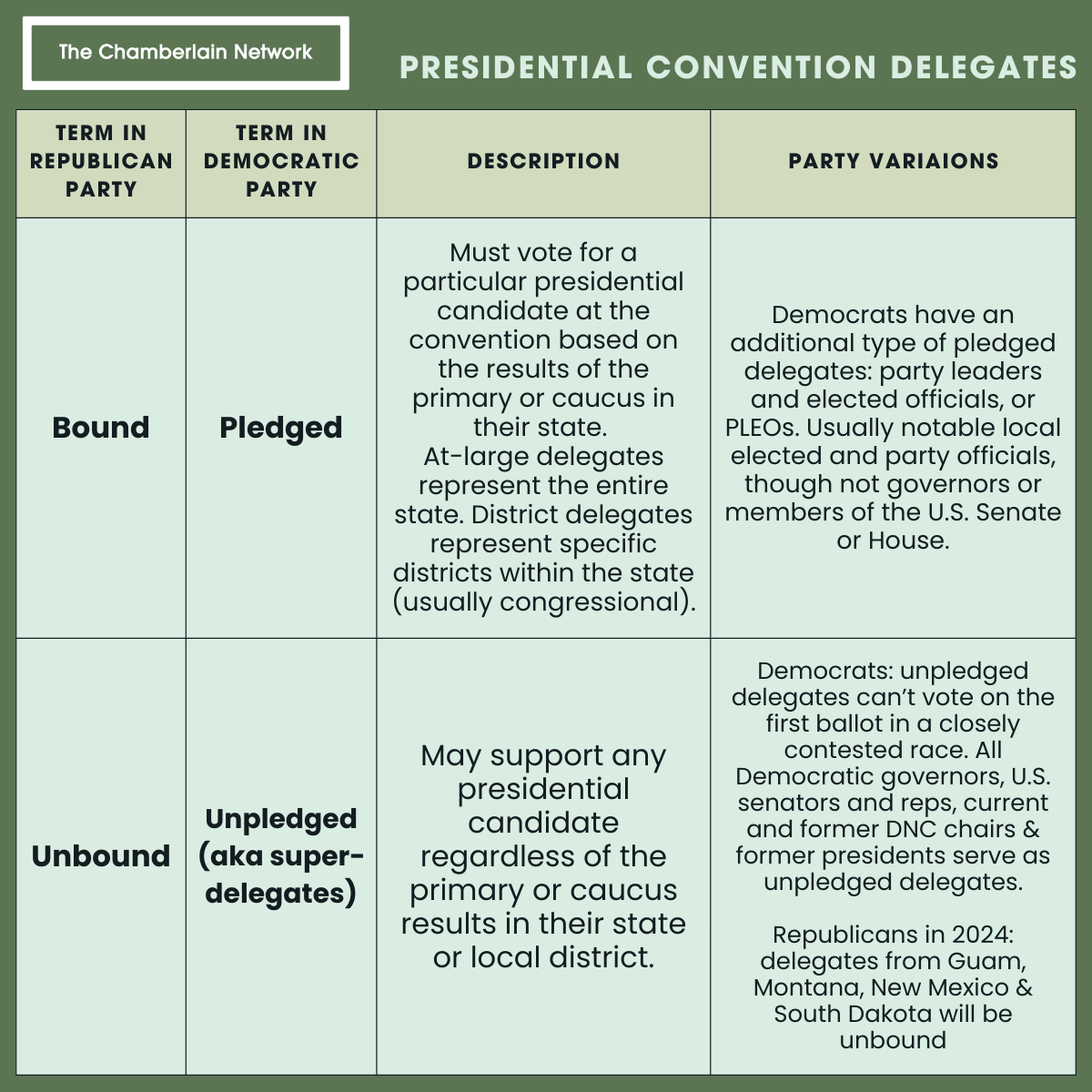

The Associated Press has a great overview of the types of delegates – there are some variations between parties, so we’ve captured the high level below:

Another highlight from Brookings:

Have conventions always functioned this way?

No, the current process has evolved several times. As Scott Piroth shares “Throughout most of American history, party leaders determined presidential nominees.” The primary system emerged in the early 20th century, but wasn’t used as the main mechanism to choose candidates until the 1972 presidential election. This was largely due to the 1968 Democratic Convention (also held in Chicago where this year’s Democratic Convention will be) – if you want a history deep dive, NPR explains how then Vice President Hubert Humphrey was nominated despite winning no delegates in that year’s primaries, nor even entering any. Humphrey’s loss, and the aftermath of the convention, was the impetus for a party commission that recommended changes to the delegate selection system. Those changes were instituted in 1972 and became the primary and caucus process that was eventually adopted by both major parties.

How were the Democrats able to change their nominee from Joe Biden to Kamala Harris?

When President Joe Biden decided to drop out of the 2024 presidential race, he was technically not the formal party nominee because the Democratic Convention had not voted to nominate him. There was some thought after his departure that the Democrats would see an open convention – when no clear leader has won the majority of delegates. However, before President Biden left the race, Democratic delegates announced their intention to move their support to Kamala Harris in a series of state announcements. Within 2 weeks, Harris had secured enough delegates to ensure the nomination.

Why did the Democrats hold a virtual roll call vote in advance of the Democratic National Convention?

To ensure they named their candidate prior to certain state ballot deadlines. The roll call vote was held over several days culminating on August 5, and Vice President Kamala Harris received enough delegates at the roll call vote to become the Democrats’ 2024 presidential nominee.

Other News We’re Reading

“For those of us predisposed to service, the idea of walking away with more left to give is unnerving.”

In Politico, part-time National Guard Officer Davis Winkie reflects on VP candidate Tim Walz’s retirement

“Our election officials and workers are public servants working on the frontlines of our democracy to make sure that every vote is counted”

U.S. Senator Alex Padilla and 21 fellow senators shared their concerns in a letter calling on the Department of Justice to ensure the safety of poll workers

Chamberlain Chit Chat

What is our team reading/listening to/thinking about this week outside the democracy space:

Chris: Last week was the third anniversary of the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. The event was what brought most of the founding team at The Chamberlain Network together. I recently wrote about that experiences and what I thought needed to be done in a Just Security op ed: US Is Finally Aiding Stranded Afghan Allies, But Congress Needs to Step Up

Amie: I can’t stop thinking about The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley, which boldly asks (and answers) the question “How would an Arctic explorer from 1847 (and a handful of other ‘time expats’) respond to the modern age?” – one of my favorite reads of 2024 so far

Pete: I’ve been walking around with a little less pep in my step this past week, as our collective time in Westeros came to an end with the House of the Dragon Season 2 finale airing. Currently looking for options to fill the 8+ hours a week that used to be filled with Game of Thrones podcast content. Part of that time will be filled reading Final Engagement by Christopher Izant, a Marine who deployed to the exact combat outpost in Afghanistan I was, a year later. The book covers his deployment and handing over that area to Afghan security forces. Whatever time leftover will be dedicated to Rings of Power, Season 2.

Is there a topic you’d like to see covered here? Reach out to us at info@chamberlainnetworks.us with your suggestions!